Peranakan, ẩm thực độc đáo và lâu đời của người Malaysia

- Rachel Phua

- BBC Travel

GETTY IMAGES

Khi Elizabeth Ng bảy tuổi, nơi cô ẩn náu không phải là sân chơi trong vùng hay phòng ngủ, mà là nhà bếp nằm phía sau của một ngôi nhà gỗ một tầng ở một kampong (ngôi làng) trên bờ biển đối diện với Eo biển Malacca.

Ng lớn lên ở Malacca, Malaysia và được bà ngoại nuôi dưỡng, sống với bốn anh chị em ruột và 15 anh chị em họ trong khi cha mẹ cô – nhân viên bán hàng – đi khắp Đông Nam Á.

Hàng ngày, đi học về, cô bé sẽ về nhà, hoàn thành bài tập và được ngoắc vào bếp với các chị em gái khác. Chỉ là làm các công việc lặt vặt, nhưng phải làm sao cho tinh tế, chẳng hạn như cẩn thận xắt lát lá chanh makrut tươi hay né nước sốt hoặc xi-rô đang sôi văng vào mình trong lúc khuấy nồi cà ri hoặc mứt dứa trên bếp lửa.

Công phu, tỉ mỉ

Nghệ thuật nấu ăn Peranakan, một nền ẩm thực Đông Nam Á có nguồn gốc đa văn hóa, do nyonyas (phụ nữ Peranakan) sáng tạo và phổ biến, thường mất nhiều công sức và thời gian.

Đôi khi việc chuẩn bị một món ăn phải mất đến vài ngày. Chẳng hạn món ayam buah keluak (thịt gà hầm hạt đen). Buah keluak, loại hạt xuất xứ từ rừng ngập mặn Malaysia và Indonesia, phải ngâm trong nước từ 3 đến 5 ngày, thay nước mỗi ngày, trước khi chiết xuất bột đen bên trong hạt.

Những người phụ nữ trong gia đình Ng sẽ làm thịt gà sạch sẽ rồi chặt gà ra, và dùng cối và chày để giã các nguyên liệu như nghệ, sả và củ hành để làm rempah (bột gia vị). Nhưng Ng yêu thích công việc này, ngay cả khi bà ngoại mắng cô nếu trong nồi có mùi khét. “Tôi đã học được cách tỉ mỉ và kiên nhẫn,” Ng nói.

GETTY IMAGES

Bà ngoại cô nấu nướng thành thạo dưới sự chỉ dạy của bà cố của Ng, người học nấu ăn từ bà kị. “Luôn là những người mẹ,” Ng nói.

Hiện sống ở Singapore, Ng truyền lại bí quyết về công thức nấu ăn của gia đình. “Bất cứ khi nào tôi nấu nướng, nó gợi lại những ký ức khi tôi ở trong bếp với Ngoại.” Vào những dịp cuối tuần, nữ giám đốc dịch vụ tài chính này mở lớp tại nhà để dạy những người lớn háo hức học làm món khai vị, nước sốt, nước chấm, tráng miệng và đồ ăn nhẹ, từ nasi ulam thơm (rau trộn cơm với các loại thảo mộc) đến kueh salat tan chảy trong miệng (bánh gạo nếp với sữa trứng lá dứa).

Ẩm thực Peranakan được biết đến là đầy màu sắc với đầy rau thơm và gia vị bản địa, giúp đem đến hương vị phức tạp cho hương vị các món ăn bắt mắt.

Nó có thể cay, mặn và hơi ngọt cùng lúc, như babi pongteh (thịt heo om với sốt đậu nành lên men); hoặc chua, cay và bùng nổ với vị ngọt thịt như ikan asam pedas (cá me cay).

Vì hầu hết các món đều cần hầm nguyên liệu lâu, tất cả hương vị tỏa vào nước thịt, tạo thành một hỗn hợp ngon mà bạn có thể cho vào cơm hoặc mì, hay để chấm bánh mì.

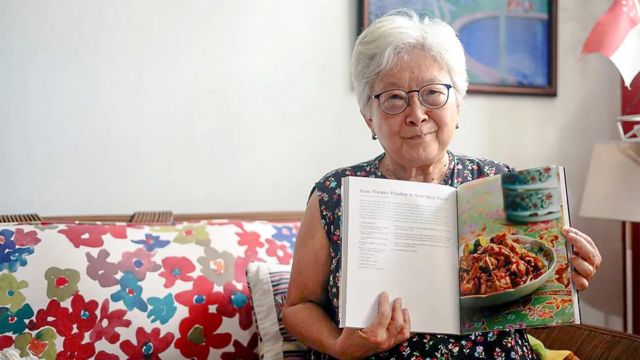

NGUỒN HÌNH ẢNH,RACHEL PHUA

Elizabeth Ng học cách nấu các món ăn Peranakan từ bà ngoại mình và nay mở lớp dạy nấu ăn tại nhà riêng ở Singapore

Món tráng miệng sống động với các sắc màu xanh lá cây, nâu, vàng và xanh lam – tất cả đều lấy màu tự nhiên từ các nguyên liệu như lá dứa, gula melaka (đường thốt nốt), nghệ và đậu xanh dương.

Ví dụ, khi làm apom berkuah (bánh tráng gạo), một vài giọt trà đậu xanh được thêm vào bột nhào và được để xoáy lên, tạo thành hình xoắn ốc xanh đẹp mắt cho mỗi cái bánh.

Ẩm thực pha trộn

Đặc trưng ở Malaysia, Singapore và Indonesia, ẩm thực của người Peranakan có nguồn gốc từ khoảng thế kỷ 15. Nó thường được coi là một trong những nền ẩm thực pha trộn đầu tiên của Đông Nam Á, kết hợp ảnh hưởng của Mã Lai, Trung Quốc, châu Âu và Ấn Độ.

Đàn ông từ Nam Ấn, Trung Quốc và châu Âu – nhiều người trong đó độc thân – vượt biển đến Đông Nam Á để làm giàu từ buôn bán theo đường biển.

Một số người trong số họ định cư ở các thành phố cảng Malacca, Penang và Singapore dọc theo Quần đảo Mã Lai, và lập gia đình với phụ nữ Đông Nam Á bản địa. Hậu duệ của những gia đình pha trộn này được gọi là Peranakan, có nghĩa là ‘sinh ra ở địa phương’.

Trong chế độ gia trưởng, phụ nữ có trọng trách xây tổ ấm. Họ nấu nướng theo phong cách họ học được từ những bà mẹ Mã Lai và Indonesia của họ: nhiều món hầm và cà ri được nấu với nhiều loại thảo mộc và hương liệu bản địa – sả, gừng xanh, lá dứa, có thể kể tên một vài loại – giúp bảo quản thực phẩm trong khí hậu nhiệt đới mà không cần làm lạnh, Lee Geok Boi, tác giả cuốn ‘In A Straits-Born Kitchen’ và các sách dạy nấu ăn khác, cho biết.

GETTY IMAGES

Nhưng họ pha trộn thực phẩm và phong cách nấu nướng của họ với các nguyên liệu được đưa tới qua con đường giao thương.

Các thương nhân Nam Ấn đã đem đến các gia vị như rau ngò và hạt thì là; còn ớt được người Bồ Đào Nha đem đến sau khi họ chiếm được Malacca vào năm 1511. Một số món ăn kiểu Mã Lai đã được biến tấu để có thịt heo (mà dân Hồi giáo bản địa không ăn) và các nguyên liệu Trung Quốc được mang đi xa, chẳng hạn như dưa chua, nấm khô và tôm, đậu tương và nước tương.

“Các bà nội trợ địa phương biến các món truyền thống Trung Quốc thành babi pongteh (thịt heo kho hầm) và mah me (mì hải sản xào), nồng nàn và đa dạng hơn so với món khởi thủy ở Phúc Kiến [tỉnh đông nam Trung Quốc],” Violet Oon, bếp trưởng Peranakan điều hành một số nhà hàng theo tên ông ở Singapore như National Kitchen by Violet Oon Singapore và Violet Oon Singapore at Jewel, cho biết.

‘Con gái phải biết nấu ăn’

Văn hóa Peranakan đến đỉnh cao vào cuối thế kỷ 19 và đầu thế kỷ 20 trước Đại suy thoái và Đệ Nhị Thế Chiến.

Người Anh đã đô hộ vùng đất khi đó được gọi là Malaya, và người Peranakan đã trở thành cầu nối giữa dân định cư thuộc địa và dân nhập cư mới từ các nước như Trung Quốc và Ấn Độ.

Cộng đồng người Peranakan học tiếng Anh, theo Kitô giáo và tích lũy của cải khi làm quan chức và chủ doanh nghiệp.

RACHEL PHUA

Lee Geok Boi và cuốn sách dạy nấu ăn của bà, In a Straits-Born Kitchen

Nhiều gia đình Peranakan tinh hoa thuê người hầu. Khi có thêm thời gian rảnh, các bà nội trợ nấu nướng và thử nghiệm trong bếp. “Chính sự kết hợp sáng tạo, của cải và cởi mở đã tạo ra nền ẩm thực pha trộn tuyệt vời,” Tiến sĩ Lee Su Kim, nyonya thế hệ thứ 6, vốn viết sách hư cấu và sách thông tin về văn hóa Peranakan, cho biết.

Trong thời kỳ này, mặc dù các cô gái Peranakan nằm trong số những phụ nữ đầu tiên được đi học, nhưng các kỹ năng gia đình như nấu nướng vẫn là phần thiết yếu trong quá trình nuôi dạy họ – học nấu ăn để chuẩn bị lấy chồng là điều đáng tự hào.

Oon cho biết mẹ của những chàng trai trẻ trong độ tuổi kết hôn sẽ đến thăm những người bạn có con gái trạc tuổi để nghe âm thanh các cô gái dùng chày và cối giã gia vị trong bếp. Nếu tiếng giã nghe có vẻ chính xác, thì cô gái đó được tin là có thể nấu ăn ngon.

GETTY IMAGES

“Đó không chỉ là hương vị, mà còn là màu sắc, sự đa dạng và khéo léo trong cách trình bày,” Lee Su Kim nói. Chẳng hạn Kueh (bánh) phải được cắt cẩn thận thành hình kim cương nhỏ bằng dao có răng cưa, được để gọn gàng trên chén dĩa sứ khi khách đến.

Sau Đệ Nhị Thế Chiến, ý nghĩ phụ nữ phải là nội tướng dần biến mất. Phong trào nữ quyền ngày càng lan rộng có nghĩa là một số phụ nữ trẻ cố tình tránh việc bếp núc.

Ví dụ, Oon nói mẹ cô, là thư ký, chưa bao giờ học nấu ăn cho đến khi đã lớn tuổi. “Đối với mẹ tôi đó là huy hiệu danh dự khi nói rằng ngay cả luộc trứng bà còn làm không được,” cô nói.

Nhưng khi còn trẻ, lo rằng mình sẽ không được nếm những món mình yêu thích khi các dì trở nên già cả hay qua đời, Oon quyết định học nấu những món Peranakan mà cô thích khi còn nhỏ.

Nhưng không phải phụ nữ nào cũng quay lưng với bếp núc. Thật ra, chính phụ nữ đã phổ biến ẩm thực Peranakan đến quần chúng.

Một số phụ nữ Peranakan đã dạy nấu ăn từ những năm 1950 đến 80 để kiếm tiền.

Trước đó, vào thập niên 1930, các công thức nấu ăn Peranakan bắt đầu có trong sách nấu ăn, Geok Boi nói. Năm 1931, cuốn YWCA of Malaya Cookery Book là sách dạy nấu ăn bản địa đầu tiên được xuất bản và giới thiệu một số công thức Peranakan như thịt heo sambal (thịt cay), hati babi bungkus (gan heo viên) và vindaloo (cà ri thịt cay), cùng với các công thức khác.

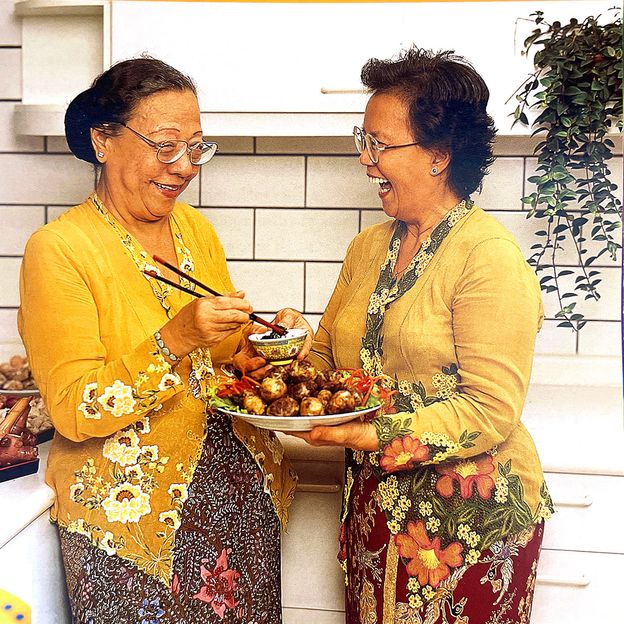

NGUỒN HÌNH ẢNH,VIOLET OON/A SINGAPORE FAMILY COOKBOOK Hai người dì của Violet Oon với món ăn hati babi bungkus (gan viên chiên)

Sách dạy nấu ăn đầu tiên tự gọi là Peranakan là tác phẩm của bà Lee: ‘Công thức nấu ăn Nonya và các công thức nấu ăn yêu thích khác’.

Nó được bà Chua Jim Neo (còn được gọi là bà Lee Chin Koon sau khi bà lấy chồng) và là thân mẫu của Thủ tướng Singapore đầu tiên Lý Quang Diệu, tự xuất bản vào năm 1974.

Một cuốn sách nấu ăn khác giúp phổ biến ẩm thực Peranakan là ‘Công thức nấu ăn yêu thích của tôi’ của Ellice Handy, giáo viên khoa học đã xuất bản nó vào năm 1952 để gây quỹ cho Trường nữ sinh Methodist ở Singapore, nơi bà dạy. Ngày nay, cuốn sách này vẫn đang được in thêm.

Ngày nay, phụ nữ trên khắp quần đảo Mã Lai đang thể hiện tài năng và khả năng của họ trong các nhà hàng Peranakan nổi tiếng, từ Nancy’s Kitchen của Nancy Goh, một tên tuổi vững vàng ở Malacca từ năm 1999, cho đến Annette Tan, vốn thúc đẩy quán ăn chuyên phục vụ các bữa ăn mang tính riêng tư, Fatfuku.

“Là người Peranakan và là phụ nữ, vẫn làm công việc thỏa mãn đầu lưỡi đem lại cho tôi niềm vui tột độ,” Oon nói. “Đối với một người phụ nữ – nấu ăn không chỉ là để ngon miệng… ăn uống là cốt lõi để tạo ra sự sống.”

GETTY IMAGES

Nasi kerabu (một kiểu món nasi ulam ăn với cơm xanh) là một món ăm thơm ngon đậm chất Peranakan

Tuy nhiên, nấu được đồ ăn Peranakan không còn là cái tạo nên bản sắc phụ nữ. Ngày nay, nhiều babas, hay đàn ông Peranakan, cũng nấu nướng và có người đứng đầu các nhà hàng, chẳng hạn Malcolm Lee và nhà hàng Candlenut được gắn một sao Michelin của ông ở Singapore, và giám khảo MasterChef Singapore Damian D’Silva, người điều hành Rempapa cũng ở Singapore.

Sáu trăm năm trôi qua, ẩm thực Peranakan tiếp tục tồn tại và phát triển. Dù là được đãi ở nhà hàng hay tại nhà, đối với người Peranakan ngày nay, các công thức được truyền qua nhiều thế hệ là lời nhắc về di sản phong phú, phức tạp và mối liên hệ của họ với các bữa cơm gia đình.

“Đó là một phần đẹp và độc đáo của nền văn hóa mà bạn không muốn đánh mất,” Lee Su Kim nói.

Southeast Asia’s 600-year-old fusion cuisine

When Elizabeth Ng was seven, her hideout wasn’t the local playground or her bedroom, but the kitchen tucked at the back of a single-storey timber house in a beachside kampong (village) facing the Malacca Strait.

Ng grew up in Malacca, Malaysia, and was raised by her maternal grandmother, living with her four siblings and 15 cousins while her parents travelled around Southeast Asia as salespeople. After school ended for the day, she would go home, finish her homework and be beckoned into the kitchen with the other girls. The tasks were menial but had to be handled delicately, like carefully slicing fresh makrut lime leaves or dodging splashes of burning gravy or syrup while stirring a pot of curry or pineapple jam over a flame.

Peranakan cooking, a Southeast Asian cuisine with multicultural roots, created and popularised by nyonyas (Peranakan women), is often labour-intensive and time-consuming. Sometimes it takes several days to prepare one dish. Take ayam buah keluak (chicken and black nuts stew) for instance. The buah keluak, a nut native to Malaysian and Indonesian mangroves, has to be soaked in water for three to five days, changing the water every day, before extracting the black paste inside the nuts.

The women in Ng’s family would also clean and cut whole fresh chickens, and use a mortar and pestle to pound ingredients such as turmeric, lemongrass and shallots to make a rempah (spice paste). But Ng enjoyed the work, even when her grandmother chided her if there was a burnt smell coming from the pot. “I learnt to be meticulous and patient,” Ng said.

Dishes like ayam buah keluak (chicken and black nuts stew) take several days to prepare (Credit: PixHound/Getty Images)

Her grandmother had mastered cooking under Ng’s great-grandmother, who had learned from her great-great-grandmother. “It was always mothers,” Ng said.

Now living in Singapore, Ng is passing on the secrets of her family recipes. “Whenever I cook, it brings back memories of spending time in the kitchen with my grandmother.” On weekends, the financial services executive holds classes at her home, teaching eager adults how to make appetisers, gravies, dips, desserts and snacks, from the aromatic nasi ulam (a rice salad with mixed herbs) to a melt-in-your-mouth kueh salat (a cake made with glutinous rice and pandan custard).

Peranakan food is known to be colourful and chockfull of local herbs and spices that give the eye-catching dishes their complex flavours. They can be spicy, salty and slightly sweet at the same time, like babi pongteh (pork braised with fermented soybean gravy); or sour, spicy and bursting with umami such as ikan asam pedas (spicy tamarind fish). Since most dishes require the ingredients to stew for long periods of time, all their flavours are released into the gravies, creating a tasty, indulgent mixture you can pour over rice or noodles, or dip your bread into.

Elizabeth Ng learned to cook Peranakan food from her grandmother and now teaches classes in her Singapore home (Credit: Rachel Phua)

Desserts come in vivid shades of green, brown, yellow and blue – all dyed naturally using ingredients such as pandan leaves, gula melaka (palm sugar), turmeric and blue pea. For example, when making apom berkuah (rice flour pancakes), a few drops of blue pea tea are added to the batter and swirled to give each pancake a pretty blue spiral.

Unique to Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, Peranakan food originated around the 15th Century. It is often considered one of Southeast Asia’s first fusion cuisines, mixing Malay, Chinese, European and Indian influences.

Men from South India, China and Europe – many of them single – had sailed to Southeast Asia in search of riches from sea trade. Some of them settled in the port cities of Malacca, Penang and Singapore along the Malay Archipelago, and started families with the local Southeast Asian women. Descendants of these blended families were called Peranakan, which means “local born”.

Under a patriarchal system, the women were in charge of the home. They cooked in a style they had learned from their Malay and Indonesian mothers: lots of stews and curries cooked in a plethora of local herbs and aromatics – lemongrass, blue ginger, pandan leaves, to name a few – which helped to preserve the food in a tropical climate without refrigeration, said Lee Geok Boi, author of In A Straits-Born Kitchen and other cookbooks.

Peranakan desserts come in vivid shades of green, brown, yellow and blue (pictured: pulut tai tai) (Credit: MielPhotos2008/Getty Images)

But they blended their food and cooking styles with ingredients introduced through trade. South Indian traders brought spices like coriander and cumin; while chillies were brought by the Portuguese after they captured Malacca in 1511. And some Malay-style dishes were tweaked to include pork (which the local Muslims would not eat) and Chinese ingredients that travelled well, such as pickled vegetables, dried mushrooms and shrimp, taucheo (fermented soybean paste) and soy sauce.

“The local wives transformed [traditionally Chinese] dishes into babi pongteh [braised pork stew] and mah mee [stir-fried seafood noodles], which were more robust and varied than the original Fujian [a province in south-eastern China] dishes,” said Violet Oon, a Peranakan chef who runs several eponymous restaurants in Singapore such as National Kitchen by Violet Oon Singapore and Violet Oon Singapore at Jewel.

Peranakan culture reached its zenith in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries before the Great Depression and World War Two. The British had colonised what was then called Malaya, and the Peranakans became a bridge between the colonial settlers and newer immigrants from countries like China and India. The Peranakan community learned English, embraced Christianity and amassed wealth as bureaucrats and business owners.

Lee Geok Boi holding her recipe book, In a Straits-Born Kitchen (Credit: Rachel Phua)

Many elite Peranakan families employed servants. With more spare time, the wives were able to cook and experiment in the kitchen. “It was the combination of innovation, wealth and openness that led to an amazing fusion cuisine,” said Dr Lee Su Kim, a sixth generation nyonya who has written fiction and nonfiction books about Peranakan culture.

Though Peranakan girls were among the first females to be educated during this period, domestic skills like cooking were still an essential part of their upbringing – it was a matter of pride that they learned to cook in preparation for marriage.

Oon said mothers of young men of marriageable age would visit friends who had daughters around the same age to hear the sound of the girls pounding spices in the kitchen with their mortar and pestle. If her pounding sounded correct, the girl was believed to be able to cook well.

Peranakan dishes like ikan asam pedas (spicy tamarind fish) can be sour, spicy and bursting with umami (Credit: i’am/Getty Images)

“It’s not just about taste, but also colour, variety and finesse in presentation,” said Lee Su Kim. Kueh (cake) had to be carefully cut into small diamond shapes with a serrated knife, displayed neatly on fine porcelain, when guests came, for example.

After World War 2, the idea that women had to be domestic goddesses gradually faded away. A growing embrace of feminism meant that some younger women deliberately avoided the kitchen.

Oon, for example, said her mother, a secretary, never learned to cook until much later in life. “It was like a badge of honour for my mother to say that she could not even boil an egg,” she said. But as a teenager, worried she wouldn’t be able to taste her favourite dishes when her aunts got older or passed on, Oon decided to learn to cook the Peranakan dishes she loved as a child.

But not all women snubbed cooking. In fact, it was women who popularised the cuisine among the masses. Some Peranakan women taught cooking classes between the 1950s and ’80s to earn money. Before that, in the 1930s, Peranakan recipes began to appear in cookbooks, said Geok Boi. In 1931, The YWCA of Malaya Cookery Book was the first local cookbook to be published and featured several Peranakan recipes like pork sambal (spicy pork), hati babi bungkus (pig liver balls) and vindaloo (spicy meat curry), alongside other recipes.

Violet Oon’s aunts sharing a plate of hati babi bungkus (fried liver balls) (Credit: Violet Oon/A Singapore Family Cookbook)

The first cookbook to label itself Peranakan was Mrs Lee’s Cookbook: Nonya Recipes and Other Favourite Recipes. It was self-published in 1974 by Chua Jim Neo (also known as Mrs Lee Chin Koon after she married), the mother of Singapore’s first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew. Another cookbook that popularised Peranakan cooking was My Favourite Recipes by Ellice Handy, a science teacher who had it published in 1952 to raise funds for the Methodist Girls’ School in Singapore, where she taught. The book is still in print.

Today, women across the Malay archipelago are showcasing their talent and skill in well-known Peranakan restaurants, from Nancy Goh’s Nancy’s Kitchen, a stalwart in Malacca since 1999, to Annette Tan, who spearheads Peranakan private dining venue Fatfuku.

“As a Peranakan and a woman, it gives me ultimate pleasure to be still performing the duties of pleasuring the taste buds,” Oon said. “For a woman – cooking food is not only about deliciousness… food is the very essence of providing life.”

Nasi kerabu (a type of nasi ulam with blue rice) is an aromatic Peranakan dish (Credit: simon2579/Getty Images)

Nevertheless, being able to cook Peranakan food is no longer an identity marker for women. Many babas, or Peranakan men, are also cooking it and some of them helm restaurants today, such as Malcolm Lee and his one Michelin-starred restaurant Candlenut in Singapore, and MasterChef Singapore judge Damian D’Silva, who runs Rempapa also in the city.

Six-hundred years on, Peranakan continues to endure and evolve. Whether served in restaurants or in the home, for modern-day Peranakans, the delicious recipes passed down over generations are a reminder of their rich, intricate heritage and the connection they have over family meals.

“It’s such a beautiful and unique part of the culture you don’t want to lose,” said Lee Su Kim.