What is the ‘ideal’ female body shape?

Fashion has long seen the female body as a malleable entity, something to be moulded according to the dictates of complex social codes or the fickle whims of the fashion industry.

By analysing the changing fashionable silhouette from the 18th Century to the present day, a new exhibition at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York (FIT) argues that the fashionable body has always been a cultural construct and one that needs to be challenged if we are to reach a greater acceptance of body diversity.

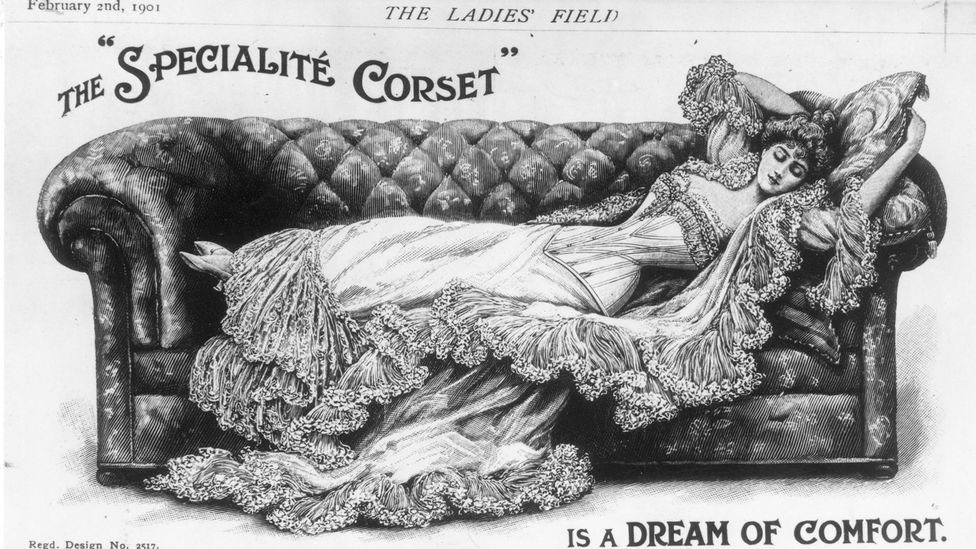

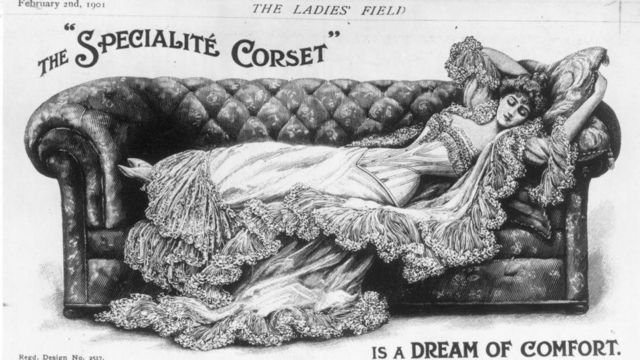

The wearing of stays (a laced underbodice) by the fashionable elite was considered essential – and not just to maintain a slender silhouette (Credit: Getty)

In the 18th Century the notion of a fashionable body was of concern primarily to the elite.

The wearing of stays (laced underbodice) was considered essential, but as curator Emma McClendon points out, this was not simply to make the wearer appear more slender.

Their widespread use was, she explains, “much more complex and related to cultural notions of propriety, class and a woman’s physicality.”

There was a prevailing belief that women’s bodies were inherently weak and in need of support – Emma McClendon

Being ensconced in stays created a uniquely rigid carriage. By mastering an elegant gait whilst constrained in such an uncomfortable garment was a sign of breeding. “There was also a prevailing belief during the period that women’s bodies were inherently weak and in need of support,” says McClendon. These ideas were challenged by some of the leading writers and thinkers of the day, with the philosopher and writer Rousseau seeing stays as a particularly apt metaphor for the social institutions constraining the individual – but his views had little impact.

The corset created a uniquely rigid carriage – mastering an elegant gait while constrained was seen as a sign of breeding (Credit: Getty)

It wasn’t until the aftermath of the French Revolution, when appearing aristocratic was decidedly frowned upon, that stays briefly lost their hold on the female imagination as they embraced the more forgiving, high-waisted empire line. However, even then some form of support garment would be worn.

The return to a nipped-in waist, shown to its best advantage by the voluminous crinoline, in vogue from 1845 to 1870, drew attention to the upper body, which was considered “the most precious,” according to Denis Bruna, curator of the fashion department of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

“In Western culture the lower parts of the body are not considered worthy, which is why women’s legs have been hidden for centuries under skirts and petticoats.”

If a man could afford to dress his wife in crinoline – which required vast amounts of fabric – it would indicate substantial income (Credit: Alamy)

The style was also the perfect way for the rising bourgeoisie to show off their wealth. Men’s attire was relatively subdued at the time but if a man could afford to dress his wife in a crinoline, which required vast amounts of fabric and the help of a servant to put on, it would indicate access to a substantial income.

Pressure to conform

The appearance of the bustle, which gave prominence to the rear, from 1870 onwards coincided with an era in which fashion was becoming progressively more democratised, as technical advances and the rise of the department store meant that different social classes were buying similar styles, thus creating a certain standardisation of the ideal silhouette and creating a pressure to conform among all social classes.

The bustle, which gave prominence to the rear, coincided with an era when fashion was becoming more democratised (Credit: The Museum at FIT)

So although dress-reform activists and doctors had been warning against the harmful effects of corsetry for decades, when it became available to the masses, women flocked to buy them. However the fact that many advertisements offered them in sizes from 18 – 30 inches (45.72 – 76.2cm) makes it clear that many women did not meet the slender ideal.

The early 20th Century saw the aesthetic dress movement, typified by elegant flowing gowns created by the department store Liberty, attempt to liberate women from the confines of the corset.

It was a style favoured in artistic circles but considered eccentric by the general public, and even those who chose to adopt the fashion rarely wore it outside the confines of the home.

A metallic dress by the House of Paquin has a waist measurement of 31 inches, proving that some designers were catering to larger sizes (Credit: The Museum at FIT)

However much the fashion press wanted to ignore them there have always been stylish larger women

It wasn’t until the flapper styles of the 1920s came into fashion that conventional corsetry began to lose favour. Although McClendon is at pains to point out that it is “a common misconception that women stopped wearing corsets and were suddenly ‘free.’” The new styles required a lithe androgynous body achieved by wearing a hip-slimming girdle, which although certainly more comfortable still created an artificial body shape.

Women for whom the look was impossible to achieve found other ways to be fashionable. The exhibition features a pair of purple-and-orange crepe pyjamas that have a 40-inch (101.6 cm) waist, proving that however much the fashion press wanted to ignore them there have always been stylish larger women.

Christian Dior dramatically broke away from convention with his ‘New Look’, which emphasised a nipped-in waist and prominent bust (Credit: Alamy)

And although the 1930s heralded the return of the waist with body-skimming bias cut gowns, it is clear that some designers were catering to women who were larger than the fashion images of the day may have us believe. A stunning metallic-silk dress by the House of Paquin has a waist measurement of 31 inches (78.74 cm).

Embracing diversity

During the 1940s broad shoulders and narrow hips were popularised by the film costume designer Gilbert Adrian and the silhouette dominated the decade, until Christian Dior dramatically broke away from it with his ‘New Look’, which emphasised a prominent bust and nipped-in waist and required up to 20m (65.62ft) of fabric. “He wanted to create dresses that were a response to the poverty of the war period,” says Bruna. This ultra-feminine aesthetic came to symbolise the 1950s.

The waifish model Twiggy epitomised the androgynous look fashionable in the 1960s (Credit: Getty)

The 1960s saw the return of the boyish, androgynous figure epitomised by the coltish model Twiggy but, unlike the 1920s, the more revealing clothing of the period, such as Rudi Gernreich’s shift dress with plastic side panel, made the wearing of support garments virtually impossible.

Corsets and girdles may have fallen out of favour, but women faced a new set of constraints as increasing emphasis was put on diet and exercise throughout the 1970s and 80s in order to maintain the fit, toned body required for the fluid sensual designs of Halston or the body-conscious dresses of Thierry Mugler.

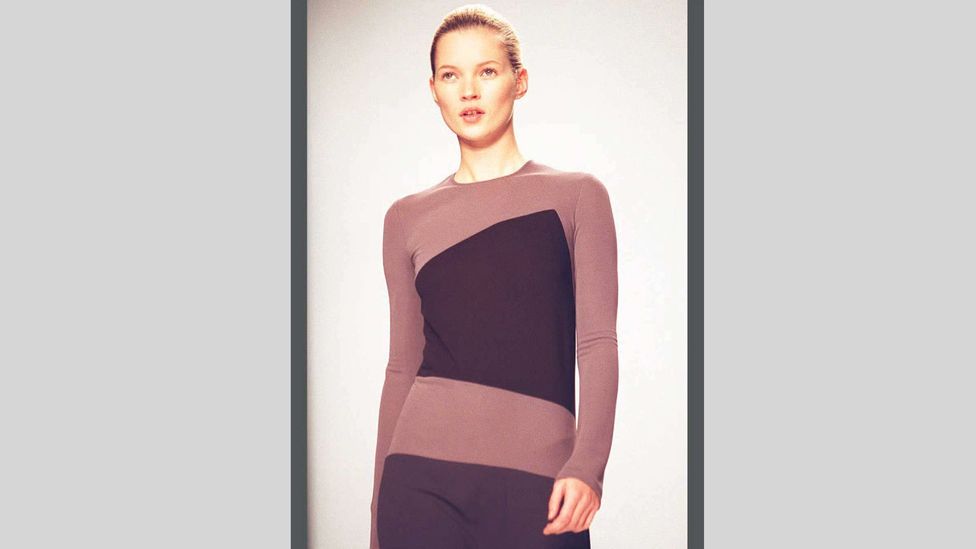

Fashion magazines championed slender bodies with paradoxically large breasts in the 1980s, a look achievable to most only via surgery, and then the waifish extreme of Kate Moss in the 1990s.

Fashion magazines continued to champion slender bodies, such as the extremely thin look popularised by Kate Moss look in the 1990s (Credit: Getty)

The rise of social media has gradually begun to change the way people consume and engage with fashion

Although a slender physique still dominated much of the fashion industry at the beginning of the 21 st Century, the rise of social media has gradually begun to change the way people consume and engage with fashion. Personal style blogs and platforms like Instagram and Twitter are opening up the industry to an ever-greater cross-section of people.

Brands such as Becca McCharen-Tran’s label Chromat have embraced a more inclusive view of the fashionable body (Credit: Alamy)

Certain brands have enthusiastically embraced a more inclusive view of the fashionable body. Designer Becca McCharen-Tran’s label Chromat has some of the most diverse catwalk shows in the industry with models spanning different races, sizes and gender identities. An outfit from 2015 wittily plays on the construction of historic undergarments emphasising McCharen Tran’s interest in ergonomic bodies of all sizes.

Christian Siriano includes plus-size models in his catwalk show and makes clothes up to size 26. When the actress Leslie Jones complained on Twitter that no label would dress her because of her size, Siriano said he would be proud to do so and created a stunning red gown.

Designer Christian Siriano made a red gown for the actress Leslie Jones when she complained on Twitter that no label would dress her due to her size (Credit: The Museum at FIT)

This episode sparked a debate about the marginalisation of certain body types by contemporary brands, and it is a debate McClendon clearly believes needs to continue.

“It is not our bodies that are wrong, it is the sizing system that is wrong,” she says. “Until we acknowledge the problems in the current system, we cannot begin to fix it.”

Cơ thể phụ nữ như thế nào là quyến rũ nhất?

Cath Pound BBC Culture 28 tháng 4 2018

FIT

Từ lâu, ngành thời trang đã xem cơ thể phụ nữ là thứ có thể nhào nặn dựa theo những quy tắc xã hội phức tạp hoặc theo ý thích của ngành thời trang, là thứ vốn thường xuyên biến đổi.

Hồi đầu năm 2018, Học viện Thời Trang Công nghệ ở New York (FIT) có cuộc triển lãm các mẫu đồ lót và quần áo kể từ thế kỷ 18 đến nay.

Dựa trên những phân tích về các đổi thay thời trang qua thời gian, triển lãm chứng minh rằng quan niệm như thế nào là một cơ thể đẹp, hợp thời hay hoàn hảo chỉ luôn là một sản phẩm văn hóa, và cách nhìn đó cần phải bị thách thức nếu như ta chấp nhận thực tế là cơ thể con người tồn tại dưới rất nhiều vóc dáng khác nhau.

GETTY IMAGES Trang phục ở nhà (trang phục lót ren) dành cho giới tinh hoa từng được coi là nhất thiết phải có chứ không chỉ để duy trì vóc dáng mảnh khảnh

Vào thế kỷ 18, giới thượng lưu rất quan tâm tới kiểu dáng.

Đồ mặc ở nhà với trang phục lót ren từng được coi là nhất thiết phải có, nhưng như giám tuyển Emma McClendon chỉ ra, chúng không chỉ nhằm khiến người mặc trông có vẻ mảnh mai hơn.

Kiểu thời trang này được sử dụng rộng rãi, bà giải thích, “phức tạp hơn nhiều, liên quan đến ý niệm về sự duyên dáng trong ứng xử, thể hiện địa vị xã hội và thước đo sức khỏe của người phụ nữ.”

Trang phục gò bó khiến phụ nữ thời đó có cách đi lại cứng nhắc rất đặc trưng.

Người ta cho rằng việc vẫn giữ được vẻ tao nhã trong khi phải bó buộc trong những chất liệu vải không thoải mái là dấu hiệu cho thấy người đó sẽ thực hiện rất tốt thiên chức làm mẹ.

“Có thời người ta còn tin là trong kỳ kinh nguyệt, cơ thể người phụ nữ sẽ rất yếu ớt và cần phải được hỗ trợ,” McClendon nói.

GETTY IMAGES

Corset tạo ra một dáng vẻ cứng nhắc – những người phụ nữ nào vẫn giữ được vẻ tao nhã duyên dáng trong bộ đồ gò bó này được coi là sẽ thực hiện rất tốt thiên chức làm mẹ

Mãi cho đến sau thời Cách mạng Pháp, cách nhìn nhận đó mới nhạt dần. Dù vậy, ngay cả khi đó thì các bà các cô vẫn cần phải dùng một số đồ phụ kiện mặc lót bên trong.

Kiểu chít eo bó chặt, với đỉnh cao là kiểu khung váy phồng phô trương, quay trở lại và trở nên cực mốt vào thời gian 1845 – 1870.

Nó thu hút ánh nhìn vào phần thân trên, là phần được coi là vị trí “quý giá nhất” của con người, theo Denis Bruna, giám tuyển tại mảng thời trang của Bảo tàng Nghệ thuật Trang trí ở Paris (Musée des Arts Décoratifs).

“Trong văn hóa phương Tây, phần dưới cơ thể không được coi trọng cho lắm, đó là lý do vì sao trong nhiều thế kỷ, đôi chân phụ nữ thường được che kín bên dưới váy và váy lót.”

Kiểu thời trang này là cách hoàn hảo để giới trí thức mới nổi khoe khoang sự giàu có.

Trang phục của đàn ông thời này đã giảm bớt sự diêm dúa nhưng nếu ông chồng đủ tiền mua cho bà vợ chiếc váy phồng, loại váy đòi hỏi cực kỳ nhiều vải may và cần phải có người hầu giúp nàng khi mặc, thì đó là chỉ dấu cho thấy ông chồng là người có mức thu nhập phong lưu.

Áp lực xã hội

Sự xuất hiện của phụ kiện tạo độ phồng cho phần phía sau váy từ năm 1870 trở đi trùng hợp với kỷ nguyên thời trang ngày càng trở nên cấp tiến và dân chủ hơn.

Tiến bộ kỹ thuật và sự xuất hiện của các cửa hàng bách hóa khiến cho nhiều tầng lớp trong xã hội có thể mua các kiểu trang phục giống nhau, từ đó tạo ra những tiêu chuẩn nhất định về hình mẫu lý tưởng, tạo áp lực khiến các tầng lớp trong xã hội phải đua theo.

THE MUSEUM AT FIT

Vì thế, bất chấp những lời cảnh báo của các nhà hoạt động cách tân váy áo và bác sĩ về sự nguy hại của áo lót corset trong nhiều thập niên, khi sản phẩm này được bán đại trà thì các bà các cô lập tức đổ xô đi mua.

Tuy nhiên, trong thực tế thì có rất nhiều quảng cáo giới thiệu kích cỡ áo từ 18-30 inches (chừng 45,72 – 76,2cm). Điều này cho thấy hình mẫu lý tưởng thời đó là người phụ nữ phải mảnh mai, và nhiều người không đạt chuẩn này.

Đầu thế kỷ 20 là trào lưu thẩm mỹ với váy áo thướt tha, điển hình là những chiếc váy suông dài nền nã do cửa hàng Liberty tung ra, mục đích là nhằm giải phóng phụ nữ khỏi sự kìm hãm của áo lót corset.

Đó là kiểu váy được giới nghệ sĩ ưa thích nhưng công chúng số đông lại coi là lập dị. Thậm chí một số người dù đã chấp nhận kiểu thời trang này cũng hiếm khi mặc nó ra ngoài mà chỉ mặc ở nhà.

THE MUSEUM AT FIT

Một chiếc váy ánh kim do hãng House of Paquin sản xuất với eo 31 inches, cho thấy một số nhà thiết kế nhắm đến kích cỡ cơ thể lớn hơn

Mãi đến khi kiểu đầm tua rua thời thập niên 1920 trở lại thời thượng thì những chiếc áo corset bảo thủ mới dần lỗi mốt.

Tuy nhiên, phong cách mới đòi hỏi người phụ nữ phải có một cơ thể ẻo lả để có thể mặc trang phục với phần chít eo gầy gò hơn, dù đã thoải mái hơn nhiều nhưng vẫn tạo ra hình dáng cơ thể không tự nhiên.

Những phụ nữ không thể đạt được vóc dáng đó lại tìm ra cách khác để bắt kịp thời trang.

Triển lãm cũng trưng bày một bộ đồ pyjama màu tím và cam bằng vải rũ với vòng eo 40 inch (101,6 cm), cho thấy dù mảng báo chí thời trang có muốn phớt lờ thì vẫn luôn có một giới phụ nữ ăn vận đồ để thể hiện vóc dáng đẫy đà hơn.

Mặc dù thập niên 1930 báo hiệu trước sự trở lại của vòng eo với chiếc váy cắt chéo ôm sát cơ thể, nhưng rõ ràng là các nhà thiết kế đã phục vụ những phụ nữ với thân hình đẫy đà hơn so với hình ảnh thời trang thời đó mà chúng ta tưởng.

Một chiếc váy làm lụa kết hợp kim loại cực kỳ lộng lẫy do nhãn hiệu House of Paquin thiết kế có vòng eo tới 31 inches (78,74cm).

Vinh danh sự đa dạng

Trong thập niên 1940, vai rộng và hông nhỏ trở nên phổ biến do ảnh hưởng của nhà thiết kế trang phục điện ảnh Gilbert Adrian.

Hình ảnh đó tồn tại qua suốt cả thập niên, cho đến khi Christian Dior bất ngờ thay đổi hoàn toàn với bộ sưu tập “New Look” (Cách nhìn Mới), nhấn mạnh vào phần thân trên nở nang và vòng eo thắt lưng ong, và người ta cần tới 20m vải để may.

“Ông ấy muốn tạo ra những chiếc váy thể hiện sự đối lập với sự nghèo đói của thời chiến tranh,” Bruna nhận định. Nét thẩm mỹ cực kỳ nữ tính này trở thành biểu tượng vào thập niên 1950.

GETTY IMAGES

Người mẫu gầy Twiggy tiêu biểu cho dáng vẻ phi giới tính trong thời trang vào thập niên 1960

Thập niên 1960 đánh dấu sự trở lại của dáng người hơi nam tính, phi giới tính theo mẫu của người mẫu Twiggy.

Thế nhưng khác với hồi thập niên 1920, trang phục hở hang hơn trong thời kỳ này khiến người ta không thể mặc thêm quá nhiều chất liệu phụ kiện.

Corset và nịt bụng không còn được ưa chuộng nữa, nhưng phụ nữ giờ đây phải đối mặt với hàng loạt khó khăn mới vì áp lực phải giảm cân và tập thể thao liên tục trong suốt thập niên 1970 và 1980.

Bởi phải có được cơ thể thanh mảnh, săn chắc thì họ mới có thể mặc được thiết kế gợi cảm của Halston hay những chiếc đầm ôm sát cơ thể của Therry Mugler.

Các tạp chí thời trang thì vinh danh thân hình mảnh mai với bầu ngực khủng bất thường vào thập niên 1980. Dáng vẻ này gần như chỉ có thể có được nhờ phẫu thuật thẩm mỹ.

Sau đó là đến vẻ gầy gò cực đoan của Kate Moss trong thập niên 1990.

GETTY IMAGES

Tạp chí thời trang tiếp tục tôn vinh thân hình mảnh mai, như dáng vẻ siêu gầy mà siêu mẫu Kate Moss nổi tiếng thể hiện vào thập niên 1990

Mặc dù vẻ ngoài mảnh mai vẫn thống trị, khuynh loát trong thời kỳ đầu thế kỷ 21, nhưng sự trỗi dậy của mạng xã hội đã dần thay đổi cách mọi người đón nhận và hưởng ứng thời trang.

Những blog thời trang cá nhân và các mạng xã hội như Instagram và Twitter khiến ngành công nghiệp thời trang mở cửa cho các vóc dáng cơ thể đa dạng hơn bao giờ hết.

Nhãn hiệu Chromat của nhà thiết kế Becca McCharen-Tran đã có một số buổi trình diễn đa dạng nhất trên sàn diễn thời trang với người mẫu đến từ nhiều sắc tộc, kích cỡ cơ thể và giới tính khác nhau.

Christian Siriano thì đưa những người mẫu to lớn lên sàn diễn thời trang và thiết kế quần áo, với các trang phục có kích thước đến tận cỡ 26.

Khi diễn viên Leslie Jones phàn nàn trên Twitter rằng không có thương hiệu nào cô mặc vừa vì kích cỡ cơ thể cô, Siriano nói ông sẽ tự hào thiết kế cho cô và đã may một chiếc váy đỏ tuyệt đẹp.

THE MUSEUM AT FIT

Nhà thiết kế Christian Siriano may một chiếc váy đỏ cho diễn viên Leslie Jones khi cô than phiền trên Twitter không có nhãn hiệu nào có trang phục vừa kích cỡ của cô

Điều này làm dấy lên cuộc tranh luận về việc một số thương hiệu thời trang không phục vụ một số kích cỡ cơ thể nào đó, và đó là cuộc tranh luận mà McClendon tin rằng nên được tiếp tục.

“Không phải là cơ thể chúng ta có điểm gì sai, mà chính là hệ thống định cỡ cho trang phục đang sai,” bà nói. “Chừng nào ta chưa chịu thừa nhận vấn đề này thì ta chưa thể bắt đầu sửa chữa nó được.”